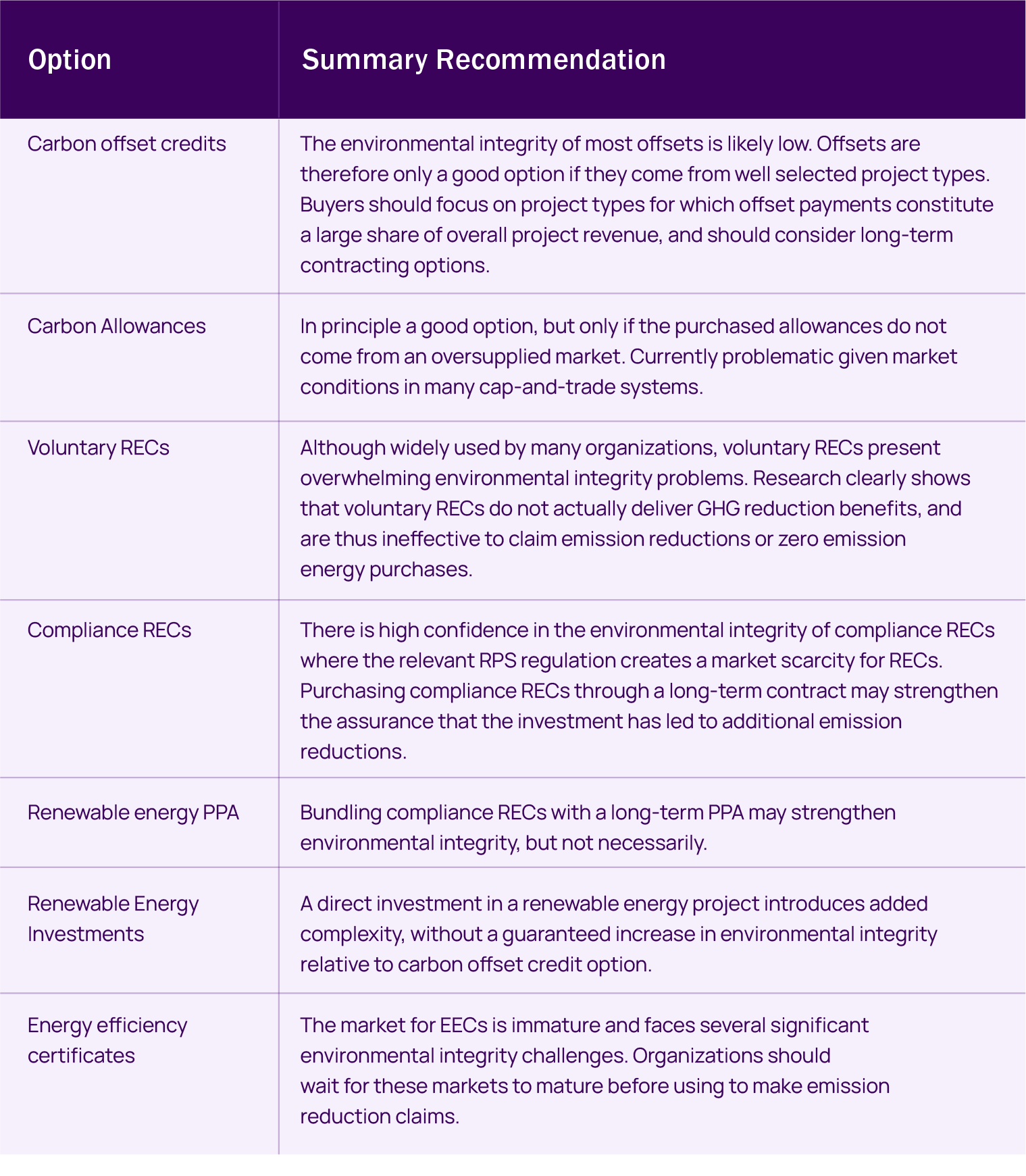

Some companies purchase other kinds of tradable instruments associated with GHG emission reduction claims or engage in transactions that include such claims. But, not all these options are equal in their effectiveness and environmental integrity.

In most cases, these purchases and transactions are not subject to certification against standards required for effective carbon offset claims. Examples of some of these “emission reduction instruments” are described below.

The findings in this website are based on researched evidence. This evidence suggests that several commonly used instruments – including voluntary renewable energy certificates (RECs), green power purchases (PPAs), and energy efficiency certificates (EECs) – should be avoided by organizations whose primary goal is to achieve credible and quantifiable GHG reduction targets. See our Clean Energy Purchasing FAQ for a detailed resource on voluntary purchasing green power claims and greenhouse gas accounting.

Voluntary carbon offsets are a viable instrument to reduce emissions, but due diligence is recommended to understand project risks and select appropriate options. Voluntary cancellation of emission allowances may be an effective option, provided the selected ETS market is not oversupplied (with allowances). Prospective buyers are advised to perform analysis to determine allowance supply within selected markets prior to making a purchase.

Types of GHG Offsetting Options and Associated Recommendations

Allowances

What are allowances?

Carbon allowances are issued by governments under emissions cap-and-trade regulatory programs. Each allowance (or emissions permit) typically allows its owner to emit one tonne of a pollutant such as CO2e.

Under a cap-and-trade system (also called emission trading systems (ETSs)), the supply of GHG allowances is limited by the mandated ‘cap’. Allowances can be allocated freely by the governing program, be purchased when auctions are held, or be purchased from other entities that have excess.

Location

The location of the emission sources covered by a cap-and-trade program depends on its scope set out in regulation or legislation. There are programs in the European Union, United States (California, Washington, and RGGI), Canada (Alberta and Quebec), China, Korea, New Zealand, and many others (visit the ICAP ETS Map for listing of cap-n-trade programs globally).

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS) is the largest cap-and-trade program covering about 45% of the EU’s GHG emissions (as of 2024).

In the United States, there are three ETSs as of 2024:

- The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI) began in 2009. RGGI is the first mandatory GHG cap-and-trade system in the United States. It includes eleven Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic states. Each state establishes its own cap and trade program that sets limits on in-state CO2 emissions from electric power plants. These programs link to a multi-state allowance market.

- The cap-and-trade program established by California’s Global Warming Solutions Act AB32 started in 2013 (CA ETS). It covers 85% of California’s GHG emissions, including the transportation sector. The California and Quebec cap-and-trade programs are linked.

- The Washington State Cap and Invest program started in 2023 following passage of the Climate Commitment Act (CCA).

Cost and Management Burden

Cost per tonne of CO2e (2024 data):

- RGGI: US$16-21

- California: US$35-43

- EU ETS: around €50-80

Most RGGI member states allow non-capped voluntary buyers to purchase and cancel RGGI allowances. The purchase of CA, WA, or EU-ETS allowances is also possible. The purchase of such allowances to make a voluntary emission reduction claim would not require a major management burden, and ongoing-management costs would be minimal. Numerous environmental commodity brokers exist that can facilitate the purchasing and retirement of allowances.

Read more on updated allowance price information and details on program price floors and other aspects of these and other cap-and-trade programs.

Environmental Integrity

Buying and retiring allowances1 from a cap-and-trade system offers an alternative to carbon credits for claiming emission reductions. This approach has the potential to avoid credit quality issues, such as non-additionality. The purchase and voluntary retirement of allowances reduce the availability of allowances in a cap-and-trade system, effectively “tightening the cap” and, in principle, reducing emissions that can be produced by sources covered under the cap (e.g., power plants, large industry, and fuel suppliers). By this logic, purchasing and retiring allowances compels cap-covered sources to achieve additional emission reductions. However, a concern with this approach is that cap-and-trade programs can have oversupplied allowance markets, or that additional allowances can be released from reserve accounts should prices rise too high.

Retiring allowances in an oversupplied market has a negligible effect.

Retiring allowances will only result in additional emission reductions to the extent that allowance markets are not over-supplied. Oversupply can build up if the emissions cap is unambitious (i.e., higher than the projected business-as-usual (BAU) emissions). In such a case, a cap-and-trade policy in a country or region actually has no significant effect on emissions from covered sources. There will be too many allowances issued by the governing regulatory authority and result in an accumulation of surplus allowances in the market. More allowances mean covered sources can emit as much as they choose.

Oversupply of allowances can also be created if the covered entities engage in more mitigation activities than required by the cap. If a cap is ambitious, over-achievement will be transient and will not lead to a build-up of surplus allowances.

In a cap-and-trade system with a long-term oversupply problem, retiring surplus allowances is one option to remove the built-up surplus but this action will not cause emission reductions. Retiring allowances from an oversupplied market may lead to additional emission reductions later in time, assuming the oversupply was temporary and that there is a scarcity of allowances in the future. However, such emission reductions would be subject to uncertainty, as reductions would depend on the continuation of the ETS and increased stringency in the ETS’s cap.

Historically, many cap-and-trade systems have been oversupplied with allowances. Many have also incorporated minimum price floors for new emission allowances sold at auction. One clear signal that a market is oversupplied is that auction prices are at or near the program’s price floor. Some ETSs also have a price ceiling, at which additional allowances are released to supply the market if auction prices reach the ceiling. Retiring allowances from a market that is trading at its ceiling will also not lead to additional emission reductions.

- The EU-ETS was oversupplied for many years, but changes to the program were instituted to neutralize that surplus (e.g., Market Stability Provisions 2019). Prices reflect these EU-ETS oversupply adjustments improving the efficacy of the program to reduce emissions. The oversupply problems with the EU ETS appear to have been resolved.

- The CA-ETS has a price ceiling and price floor. Allowances are currently trading well above the price floor, indicating that there is a scarcity of allowances.

- RGGI was severely oversupplied in the past because of a switch to natural gas from coal by many utilities and a weak economy over the baseline setting period. RGGI has a low price floor and allowance prices have traded at or slightly above this floor, indicating that there is no scarcity of allowances.

- The WA ETS only began allowance auctions in 2023. After an initial period of high prices, auction prices in 2024 have been near the price floor due to some uncertainty in the program’s political future.

Potential Risks

Concerns related to the environmental integrity of allowances due to oversupply present a significant risk – if used as an instrument to make voluntary emission reduction claims. Buyers should not make such claims based on the voluntary retirement of allowances from oversupplied cap-and-trade programs.

Social and Environmental Co-benefits

Unlike carbon credits, the purchase of allowances would not allow the purchaser to select activities with sustainable development benefits.

Outlook and Considerations

Buying and Retiring allowances from a cap-and-trade system offers an alternative to carbon credits but environmental integrity can only be ensured if allowances come from a system that is not oversupplied over the long-term.

The retirement of EU-ETS and CA allowances has become a viable option as the EU-ETS no longer appears oversupplied. RGGI is clearly oversupplied and should not be considered for voluntary allowance retirement. More time is needed to understand the future of the WA ETS. Other ETSs globally require evaluation of their supply of allowances before relying upon them as an alternative to carbon credits. Any buyer considering this option should follow developments in the selected system to track prices, allowance supply, and changes to programmatic rules that may effect the environmental integrity of using ETS allowances to make voluntary emission reduction claims.

Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)

What are RECs?

A Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) can be issued when one (net)2 megawatt-hour of electricity is generated and supplied to the grid from an eligible renewable energy resource. RECs are environmental commodities that can be traded separately from wholesale electricity markets. In Europe, an analogous environmental instrument is referred to as a Guarantee of Origin (GO).

RECs are described as representing environmental or renewable “attributes” or “benefits” associated with renewable energy generation. Unfortunately, what is meant by “attribute” and “benefit” is typically ambiguous and unspecified. Despite this ambiguity, RECs and GOs are also often treated as if buying them is the same as buying green power (e.g., electricity produced solely by renewable generation resources). Yet, there is no empirical evidence for such an ownership claim. However, some regulatory language has been crafted that attempts to treat such claims as legitimate.

The original purpose of RECs was for tracking compliance with legislated electric utility renewable generation quotas (i.e., Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPSs). But they are now also used in a voluntary context by companies and consumers to claim they have “purchased” renewable electricity. It is important to recognize that there are numerous “flavors” of RECs and REC markets. The two major categories are:

- RPS Compliance RECs: An example of which is the RECs that are often purchased by electric distribution utilities as part of a wholesale purchase power agreement (PPA) to comply with an RPS regulation. These RECs can only be issued to renewable energy facilities that meet the eligibility requirements of a jurisdictions’ RPS legislation. Many U.S. states have created classes (i.e., “flavors”) of RECs that have different definitions, include quotas for purchase by utilities, and therefore differentiated prices by REC class.

- Voluntary market RECs: Electricity consumers are typically advised—for example by the US-EPA Green Power Program or the World Resources Institute’s series of GHG Protocols—that they can “buy” electricity from renewable energy generators, versus fossil fuel-fired generators, through purchasing voluntary market RECs (see What am I receiving if I buy a voluntary REC or GO?). These voluntary RECs (and GOs) are issued to wind farms or hydroelectric generators in jurisdictions where they are not eligible to be sold for RPS compliance or because the REC market in that jurisdiction is oversupplied (i.e., the RPS goals set by lawmakers in that region are too weak to drive investment in new capacity). These RECs are typically registered with a certification program (e.g., Green-e) and may be registered with regional certificate tracking systems.

Location

Compliance RECs can be purchased from jurisdictions with RPS regulations. Voluntary RECs and GOs can be purchased by any entity anywhere, although some markets encourage purchases to occur from generation local to the buyer.

Cost and Management Burden

Cost per metric ton of CO2e (2019 data):

- Compliance RECs: prices vary across regulatory jurisdictions due to differing and changing program rules. For example, the emission reduction cost of retiring New England region (MA, CT, NH, & RI) RPS compliance RECs is estimated at roughly US$55 to $110 per metric ton of CO2. Costs are in a similar range from retiring compliance RECs from the U.S. mid-Atlantic region (PA, NJ, MD) under the PJM ISO.3 Note that some compliance REC markets are oversupplied due to weak RPS quotas as set by the government. Retiring a type of REC that is oversupplied is not a legitimate claim for avoiding emissions. Like with allowances, you can identify if a type of REC is oversupplied if its price is far below a regulatory alternative compliance penalty (ACP) value (i.e., a shortage can be identified when RECs are trading near or at the ACP value). Some RECs that come from solar generation are specifically designated with their own RPS quotas and can in some states trade at significantly higher prices.

- Voluntary RECs: The cost per ton of CO2e does not exist for voluntary market RECs because as shown below, the voluntary REC market does not affect renewable energy investment or generation. The voluntary REC market has always been massively oversupplied, and research has concluded that it is highly likely to remain so indefinitely. Voluntary market REC (wholesale) price is roughly $0.5 to $4 per MWh.

RECs that are eligible for RPS compliance can be acquired through environmental commodity brokers.

Environmental Integrity

Environmental integrity differs dramatically between purchasing voluntary market RECs and purchasing compliance REC:

- The most common underlying objective in purchasing voluntary market RECs would be to report the indirect emissions associated with its consumption of purchased electricity (i.e., Scope 2 emissions) as zero. The problem with this zero-emissions claim is that REC purchases do not reflect, nor do they necessarily alter, the emissions physically associated with or caused by a firm’s electricity use. Research has shown that there is no causal relationship between the purchase of voluntary market RECs or the growth of the voluntary REC market overall and the amount of renewable energy generated in the United States. Consequently, the evidence does not justify assigning emission factors or claiming avoided emissions based on the purchase of voluntary market RECs. The evidence clearly shows that the voluntary REC market, in its current form, lacks environmental integrity.

In contrast, some RPS compliance REC markets are likely to be causing additional renewable energy investment due to the incrementally increasing RPS goals, as indicated by their far higher certificate price. There is moderate confidence in the additionality of RPS compliance RECs for the U.S. Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. This confidence would be increased further if a buyer commits to a multi-year purchase contract.

So, purchasing and retiring compliance RECs is a credible option to claim avoided emissions when these RECs come from a REC market facing some scarcity and the REC is canceled (retired), thereby removing it from use by a utility for compliance. However, instead of claiming to have purchased “green power” and applying a zero-emission factor to a corporate GHG footprint, the purchaser should quantify the avoided GHG emissions associated with the marginal impact of this REC retirement. And, thereby quantify and claim the avoided emissions and offsetting effect of the REC retirement. The marginal impact can be estimated using a load dispatch analysis of avoided fossil generation using existing electric power industry models. There are also more simplified methods to quantify the effect of avoiding the building and operation of fossil generation. The quantification of the avoided GHG emissions would present some complexity but is unlikely to present a significant technical barrier.

Theoretically, if a cap-and-trade program overlaps with the jurisdiction of an RPS, then removal of a compliance REC from the market may not lead to additional avoided emissions. Instead, it would simply shift when and where emissions occur because total emissions are already capped. Additional avoided emissions are only achieved if the purchaser cancels allowances. If one wished to avoid any risk or criticism, a buyer could retire both compliance RECs and associated emission allowances in combination given the uncertainty in future ETS and RPS market rules. This option would result in higher costs.

Social and Environmental Co-Benefits

There is minimal risk of harm, as well as limited opportunity for co-benefits with this option of claiming avoided emissions.

Potential Risks

Voluntary market RECs present a significant reputational risk, given their proven lack of environmental integrity. Concerns around the environmental integrity of voluntary RECs have not gone unnoticed by leading companies. For example, in Google’s white paper discussing their approach to renewable energy purchasing they clearly state concerns with unbundled voluntary RECs:

“Our efforts must result in “additional” renewable power generation. We’re not interested in reshuffling the output of existing projects, and where possible, we want to undertake efforts near our data centers and operations.” (Google 2013a)

To address concerns about RECs, some companies have decided to pursue voluntary RECs bundled with long-term PPAs. Though this option is an improvement over voluntary RECs alone, companies could improve the environmental integrity of their approach by purchasing RPS compliance RECs. A long-term PPA with a renewable energy project is likely to have more environmental integrity, but it is not yet a proven approach that definitively leads to additional avoided emissions because there is little research on this approach. This lack of evidence or guidance on PPAs is a major gap that is in need of correction.

Nevertheless, several major companies purchase voluntary RECs to use them to claim they are meeting their GHG reduction and green power goals. Further, some environmental groups (e.g., Green-e, US-EPA Green Power Program, GHG Protocol Program) have been resistant to update their guidance for fear of contradicting past positions and continue to present information to companies that lack environmental integrity and leads to misleading corporate reporting.

In contrast, purchasing compliance RECs provides an opportunity to publicly distinguish an organization from the common practice of using ineffectual voluntary RECs to misleadingly claim to have avoided emissions and meet green power targets.

Conclusions

Voluntary market RECs, although currently promoted by many environmental organizations, present overwhelming environmental integrity problems. Too much of the guidance on voluntary green power purchasing and GHG emissions on this topic from organizations like the US EPA Green Power Program, CDP (formerly “Carbon Disclosure Project”), and the Center for Resource Solutions (CRS, the owner of the Green-e label) is, unfortunately, outdated and misleading. Most published guides focus on promoting the purchase of voluntary RECs and provide little or no substantiation or evidence of environmental integrity. Research shows that voluntary REC purchases are highly unlikely to result in actual environmental benefits.

The purchase of compliance RECs can be a sound option if the RPS creates a scarcity in its associated REC market. It would be equivalent to purchasing emission allowances (where the market is also not oversupplied) or high quality carbon credits. The challenge with compliance RECs involves some extra analysis to quantify the tonnes of CO2 avoided based on the MWhs of fossil generation that would otherwise have occurred. This extra layer of analysis is not necessary for the retirement of allowances or carbon credits.

Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)

What are PPAs?

This option for claiming avoided emissions is different from the previous ‘RECs by themselves’ option in that the RECs involved here remained “bundled” with an underlying wholesale power purchase agreement (PPA). The same issues differentiating voluntary versus RPS compliance RECs apply. As do the same conclusions and recommendations. Here we focus on the distinctions between the bundled and unbundled compliance REC options.

Location

Same as compliance RECs.

Cost and Management Burden

Cost per metric ton of CO2e: N/A

The cost would be negotiated as part of a PPA. Unfortunately, there is no standardized methodology currently for quantifying the avoided emissions impact of a PPA.

Environmental Integrity

The same environmental integrity issues related to differentiating voluntary versus RPS compliance RECs apply to this option. Although, by keeping compliance RECs bundled with a PPA it will be easier to procure a longer-term contract, which should increase the probability that the action will result in additional avoided emissions.

Social and Environmental Co-Benefits

There is minimal risk of harm, as well as limited opportunity for co-benefits with this option.

Potential Risks

It is increasingly common for companies to use a renewable energy PPA and retire the associated RECs to make green energy purchasing and avoided GHG emission claims. This option provides far more environmental integrity than voluntary RECs alone, but the effectiveness of the various types of PPAs requires further study to establish.

Conclusions

Although further research on the impact of PPAs on renewable energy investment and generation is needed, this option presents fewer environmental integrity problems than solely purchasing voluntary RECs. Buyers could establish a stronger claim to avoided emissions, and further reduce environmental integrity risks, by bundling and retiring under-supplied RPS compliance RECs with their PPA.

Renewable Energy Direct Investment

What are renewable energy direct investments?

This option involves directly taking a significant equity stake in a new renewable energy investment, such as a solar wind farm. This option differs from the REC options in that the purchaser would be owning part of the renewable energy project. Effectively, you would be a crediting project developer. (This approach can also be taken with project types other than renewable energy.)

The purchaser would likely need to work with an investment bank and a renewable energy project developer and provide up-front financing for the project. And then contractually put in place ownership provisions for the resulting RECs and/or carbon credits.

The same distinguishing characteristics between the voluntary REC and RPS compliance REC markets identified with the RECs option apply to this option too. A project that is within the jurisdiction of an RPS with a REC scarcity would more likely be additional if the resulting compliance RECs were retained and retired.

Location

Renewable energy projects could be located locally, in the U.S., or internationally.

Cost and Management Burde

Cost per metric ton of CO2e: Varies widely.

Becoming a direct project investor would provide the possibility of acquiring lower-cost claimable avoided emissions over the long-term, as you would be entering earlier in the process and accepting more of the upfront project risk compared to a PPA transaction.

This option would entail the largest management and transaction cost burden, although these costs may be balanced by the lower cost per metric ton of avoided emissions. Further analysis would be needed to quantify the cost of this option.

Environmental Integrity

There are recognized methodologies for quantifying the avoided emissions from renewable energy projects that have been widely used and tested under the UN Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) as well as the voluntary carbon credit market. However, unlike carbon credits, there are no independent authorities certifying that these methods have been properly applied to renewable energy investments.

The same environmental integrity issues differentiating voluntary versus RPS compliance RECs apply to this option. Evaluating the additionality of this option is not difficult if the project is within the eligibility of an RPS and the resulting RECs are retired without being used for compliance. The assessment of additionality becomes more difficult for a project that takes place outside of a jurisdiction with a binding RPS quota. In this case, it would need to be demonstrated that the investment intervention was necessary for the project to go forward. This analysis would be complicated in the United States by the uncertainty surrounding the renewal of federal tax credit for wind and solar. In these circumstances, it may be preferable to simply register a renewable energy investment as a crediting project, and therefore ensure that it meets rigorous additionality testing. Renewable energy investments are otherwise not subject to the same kinds of explicit criteria and accounting rules applied by carbon crediting programs.

Social and Environmental Co-Benefits

Same as RECs.

Potential Risks

While most universities and companies have opted to sign long term PPA for renewable energy, rather than owning and operating their own facilities, a few companies have gravitated towards the latter. For example, Apple owns and operates renewable energy generation systems at some data centers. Apple registers and retires the associated RECs to meet its voluntary emission reduction targets.

Purchasing (or investing in) compliance RECs offers the opportunity to publicly distinguish itself from the common practice in the corporate world of using voluntary RECs to meet targets.

Conclusions

Direct investment in a renewable energy project does not guarantee increased environmental integrity relative to other options. It would be easy to engage directly as an investor in a project that would have gone forward without the purchaser’s equity contribution. It would be necessary to distinguish the portion of the purchaser’s intervention that is simply looking for a return on equity versus the portion that is intended to acquire avoided emissions. From a PR perspective, it will be difficult for an organization to approach such an investment with a profit motive and credibly claim to have caused additional avoided emission. The advantages of this option are likely outweighed by its added complexity.

Energy Efficiency Certificates (EECs)

What are EECs?

Energy Efficiency Certificates (EECs), or “white tags,” are a tradable environmental commodity that represents an MWh of energy consumption avoided through an energy efficiency activity. Although far less common than RPS compliance RECs, they also serve a compliance function in select US-states and other countries where there are government-mandated quotas for energy savings. These mandates are placed on electricity distribution utilities.

In theory, EECs are analogous with carbon credits but are denoted in units of avoided energy consumption rather than avoided emissions. To be counted as an avoided emission an EEC project would need to satisfy the same quality criteria (e.g., additionality and accurate quantification) and assurance processes as a carbon crediting project.

EECs are denoted in terms of MWh of energy savings. Therefore, they would have to be converted to metric tons of avoided GHG emissions by analyzing the marginal impact of the underlying energy efficiency project on electricity generation emissions.

Given the immaturity of the market for EECs and the lack of standardization of methods for these certificates, there is limited information about this option.

Location

There is a very small compliance market for EECs. Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Nevada have allowed utilities to use and trade EECs for compliance with their energy efficiency obligations. Italy operates a national program.

Cost and Management Burden

Cost per metric ton of CO2e: N/A

Unlike the carbon credit market, there are no independent institutional mechanisms in place for EEC quality assurance. It would create a significant management burden for the purchaser.

Environmental Integrity

There are several significant challenges with EECs. The existing quantification methodologies for EECs account for historical energy use and weather effects but do not consider additionality as fully as a crediting project. Therefore, EECs can be issued to projects that are profitable and likely to be implemented in the absence of the EEC incentive (i.e., they likely lack environmental integrity).

An organization could more credibly purchase carbon credits from energy efficiency projects implemented following carbon crediting methodologies.

Social and Environmental Co-Benefits

There is minimal risk of harm.

Potential Risks

Given the immature market and lack of standardized quality assurance criteria, EECs present environmental integrity risks.

Conclusions

Theoretically, the EEC option is the same as the carbon credit option, but this option lacks a broad technical community and standardized quality assurance processes like those that support carbon credit issuance. The voluntary carbon credit market already includes numerous types of energy efficiency project types that embed credible methods for quantifying tonnes of avoided emission and address additionality. EECs are a far inferior and higher risk option compared to carbon credits.

Alternatives to Purchases

Going beyond avoided emissions and enhanced removals

Reducing global GHG emissions to 45% below 2010 levels by 2030 and net-zero by 2050—the targets identified by the 2018 IPCC report on limiting global warming to 1.5 °C and avoiding disastrous climate change impacts—will require infrastructure and societal change. Beginning this transformation does not need to wait for new science or technologies. Cost-effective climate solutions are plentiful for energy, transportation, waste, agriculture, and other GHG emitting sources. The persistent barrier is the political will to implement these solutions.

As a responsible actor, it is morally appropriate that you set your own climate protection priorities. Your voluntary emission reduction commitments can show leadership. Here is how you and your organization can meaningfully help protect the climate.

Political advocacy

Most importantly, be politically active: vote, support, and donate to initiatives and officials seeking political office who will enact and implement climate change legislation and regulations. Remind elected officials of your support through climate advocacy: lobbying, sponsorship of climate-related events, public statements, and leveraging your market power to push for legislative change. You can also encourage your employees, customers, and organizational members to join you in these efforts through phone calls, letters, petitions, and attending rallies and marches. Consider granting office holidays on election days to ease voting for employees. Beyond what guidance we can offer, think creatively – leveraging your company’s products, customer base, and values – to generate the public support necessary to pass legislation and curtail emissions while building your brand as an organization committed to a sustainable and democratic future.

Financial stewardship

The fossil fuel industry is still building pipelines, extracting coal, oil, and gas reserves. These projects are funded by many of the banks and investment managers we use, as well as the endowments that make our organizations possible. Understanding your institutional connection to fossil fuel investments can be an eye-opening experience, and an opportunity to demand agency over your money. Depending on your institution’s structure, you may be able to actively shift funds to non-fossil fuel investments or may need to take a longer-term approach: advocating within your organization for a greater level of climate responsibility through “reinvestment” of fossil fuel financing. Addressing endowments, annual budget holdings, pension funds, and ensuring climate-responsible retirement options for employees are actionable steps to exercise agency and reduce the availability of funding for fossil fuel development.

Community building

A 1.5 °C warmed world still involves many dangers, like increased damage from natural disasters and less consistent rainfall patterns. Community resilience efforts to prepare organizations and communities for the dangers they face must also be prioritized. As a member of your community, share your understanding of the threats of climate change by educating others and urging them to take action. Established communal approaches to decision-making can facilitate changes to protect against future damages and acceptance of difficult decisions in times of disaster.

Live by example

In addition, encourage your employees, customers, and organizational members to reduce their carbon footprints and live less energy-intense lifestyles. Encourage them to fly less, live in an apartment close to work, use public transportation, eat vegan, vegetarian, or less meat, insulate your home, and compost food waste. Encourage conscious consumerism – reduce the overall consumption of material goods and advocate for intentionality about the products you do purchase. Support companies committed to addressing climate change, buy long-lasting energy-efficient appliances and encourage others to do the same. Incentives, employee benefits, education, and awareness campaigns are all effective ways to promote individual sustainable behavior as an organization. There are many more tips available for improving personal lifestyle sustainability, but essential to this objective is your ability to communicate these changes to others thereby spreading these practices.

However, it is important to note that climate change is a global collective action problem that inherently will only be solved through policy, not individual acts of virtue.

Donate to support good work

Make charitable contributions to high impact environmental and social projects around the world.

A note for individuals

Addressing climate change is a large task and we must each do what we can to promote a sustainable future. That being said, even the most dedicated, energized, and brilliant among us will find their impact amplified by group membership and coalition building. Organize your neighborhood, faith-community, alumni network, rec-league sports team, dance class, and the other communities you have access to because our message is amplified when spoken by more voices.

Summary: Avoided emissions considerations

A variety of options are available to organizations to claim avoided GHG emissions through financial interventions if they deem achieving their GHG reduction target through internal reductions as too difficult. But not all these options are equal in their effectiveness and environmental integrity.

The findings in this guide are based on researched evidence. This evidence suggests that several commonly used instruments – including voluntary renewable energy certificates (RECs) and energy efficiency certificates (EECs) – should be avoided by organizations whose primary goal is to achieve credible and quantifiable GHG reduction targets. There is currently insufficient evidence to assess under what conditions renewable energy power purchase agreements (PPAs) would be expected to have environmental integrity.

Voluntary carbon credits are a viable instrument to claim avoided emissions or enhanced removals, but due diligence is strongly recommended to understand project risks and select appropriate options. Voluntary cancellation of emission allowances or compliance RECs may be an effective option, provided the selected ETS or RPS market is not oversupplied with allowances or RECs, respectively. Prospective buyers are advised to perform analysis to determine allowance or compliance REC supply within selected markets prior to making a purchase.

- The terms retiring and canceling may be used interchangeably in some contexts. In some systems canceling refers to deleting the units without using them for compliance or claiming them toward a voluntary emission reduction goal while retiring implies the use of the allowances or credits toward regulatory compliance or voluntary goals (see glossary). ↩︎

- “Net” refers to the amount of MWh used by the generation plant for its own operations. For example, a wind farm uses some of the electricity it generates to run its own systems, hence the “net”. ↩︎

- Price estimates are based on the assumption that the marginal unit displaced by additional Class I renewable generation is natural gas-fired. The cost per metric ton using solar RECs could be higher in some jurisdictions. ↩︎